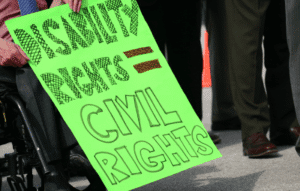

And yet, not all communities that are deeply impacted by today’s environmental hazards have been adequately recognized as a frontline community. Disabled people have been largely omitted, despite a long history of facing disproportionate consequences from pollution, climate change, wildfires, and more.

Perhaps the most obvious example of exclusion can be seen in the government’s own definition. The Environmental Protection Agency describes environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” This definition includes many communities who have long been affected by environmental hazards, and yet it continues centuries of erasure of disabled people despite being one of society’s most marginalized demographics.

How is the disability community affected by environmental hazards?

Climate Change and Emergency Response

During Hurricane Katrina, one of the first big disasters in the United States to be attributed to climate change, disabled people were disproportionately affected because their access needs were either overlooked or completely ignored. For example, there was no pre-planning for evacuating hospitals and nursing homes; most evacuation buses didn’t have a wheelchair lift, leaving many people stranded; and no alternative communication materials containing information critical to safety and survival were provided for people who identified as blind, Deaf, or hard of hearing. For those who were able to evacuate, FEMA’s temporary housing was not compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). From evacuation to communication to shelter to recovery, the process completely failed to meet the needs of the disability community, with harmful and even fatal results.

Hurricane Katrina and other natural disasters are a wake-up call, especially as climate change has accelerated the frequency and intensity of storms, flooding, and other natural disasters. However, at the local, state, and federal level, disabled people are still fighting to be accounted for in emergency response plans, even in Portland. In late 2021, a Portland auditor found that the city is unprepared to assist people with disabilities during emergencies, with Disability Rights Oregon citing many of the same issues seen seventeen years ago during Hurricane Katrina.

Wildfires

As every Oregonian knows, wildfires have intensified over the last few years. Thousands have been forced to evacuate their homes, and millions have had to endure toxic smoke-laden air. For people who already have respiratory illnesses, hazardous air can worsen existing disabilities or create new ones. On top of that, evacuation is much more complicated for people with disabilities due to both a consistent shortage of ADA-compliant housing and because the homes of disabled people are often customized to meet their individual access needs.

Power Outages

For those with disabilities, losing power can mean losing access to powered wheelchairs, elevators (leaving people stranded), oxygen generators, refrigerated medications, and more.

Pollution

Health issues are often brought up as a consequence of pollution, from cancer to asthma to heart disease. And yet, very little research has been done on how pollution affects people who already have disabilities, despite the fact that disabilities can be either exacerbated or created by pollution. Dr. Jayajit Chakraborty, a researcher and professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, wanted to address the need to understand the relationship between disability and pollution. His 2020 study in Harris County, Texas, found that people with disabilities are significantly more likely to live in neighborhoods that are close to Superfund sites and hazardous waste management facilities, making them more vulnerable to exposure.

Dr. Chakraborty’s findings also show that people with disabilities near those sites frequently have multiple marginalized identities that overlap with other environmental justice priority groups, including communities of color as well as people who are elderly. By understanding these communities through a lens of intersectionality where we account for all identities, the environmental justice movement can better respond to the needs of the people who are most affected by environmental hazards.

–

It’s impossible to solve a problem when both government agencies and nonprofits fail to acknowledge the problem even exists. If we do want a truly just and intersectional approach to environmental justice, disability must be embraced by environmental justice advocates both nationally and right here in Portland. And disabled people need to be at the table, working on solutions, alongside other impacted communities.

Bird Alliance of Oregon has been expanding its work in the disability justice arena through plans to improve accessibility at our own Wildlife Sanctuary, increasing the accessibility of our adult education programs, creating new partnerships with disability organizations, and through our policy work and advocacy. We know we have room to grow and are committed to taking an intersectional approach to ensure that all frontline communities, including the disability community, are a part of the environmental movement and solutions.